Educational Values and the Complexity of Education Systems

Exploring the value of 'inclusivity' in the Bhutanese education system

By: Matthew Schuelka

Education, like any social institution, is a complex system filled with multiple actors with multiple agendas; operating under multiple contexts, multiple policies, and a variety of institutional cultures. The educational reform industry – and I use that word deliberately – often tries to frame education within simplistic input-output equations, attempting to enact change by singling-out one input such as ‘teachers’ or ‘curriculum.’ All too often, in fact, the perceived ‘failure’ of an educational system falls squarely on the shoulders of teachers alone. These educational reform approaches nearly always fail, because an education system is organic and complex, and every input and output are never isolated or independent.

In my research on educational values in Bhutan1, and in general through my longitudinal research engagement in Bhutan since 2012, my research colleague Kezang Sherab and I have come to understand educational values through the lens of dynamic complex systems. This is building upon other work that I have done with my friend Thomas Engsig developing a complex educational systems analysis framework for analyzing educational policies, discourses, phenomenon, and the dynamics of a variety of factors that influence educational outcomes.

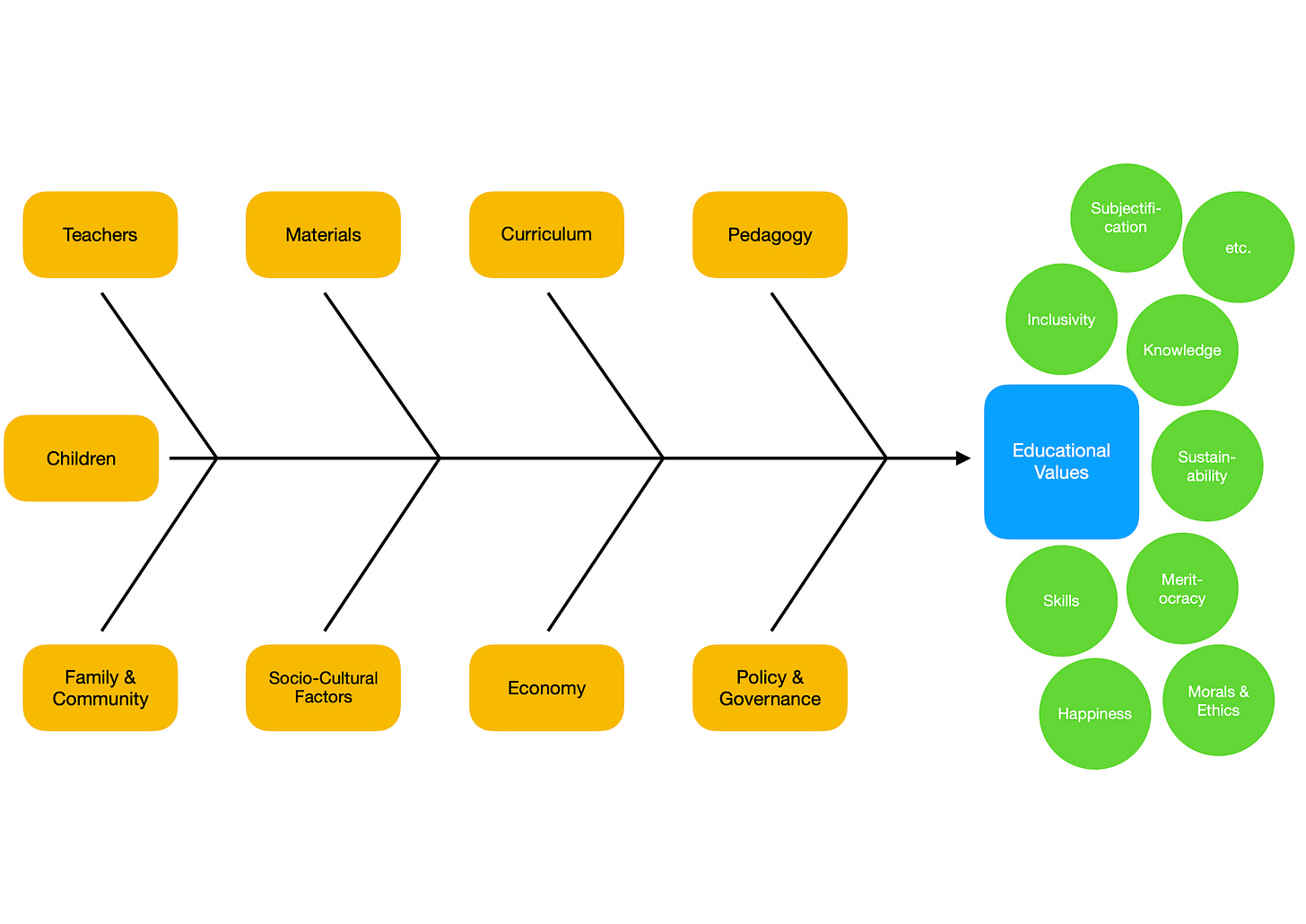

For our educational values in Bhutan project, I go further into understanding the various factors that contribute to societal and educational values as an output. I also argue that such a framework can be used to intentionally design desirable values as a product of the education system. We call this the Educational Values Evaluation and Design (EVED) framework, as seen below:

The EVED framework is a way of breaking down various elements in a complex system, and understanding how each contributes towards producing educational values. These elements are also interconnected and interrelated, although it was cleaner to draw this as an Ishikawa diagram rather than a lot of lines going everywhere. The values on the right side of the figure above are various examples of educational and societal values that an educational system may (or may not) want to produce or see exhibited in their graduates. The values listed are certainly not exhaustive here.

As an illustration of how the EVED framework functions, I will briefly explain the value of ‘inclusivity’ and how various elements in the Bhutanese educational system align or misalign in producing this value. This is only a small aspect of this research project, and many more publications are set to come out related to this in the next year or two.2

Educational policy in Bhutan specifically expresses that Gross National Happiness be central to its values within the system, and other progressive values such as ‘Green Schools,’ ‘21st Century Schools,’ and the ‘Education Mandala’ have all suggested that values such as inclusivity are central to the societal values that the Bhutanese education system espouses. Bhutan has also signed many international treaties such as the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, that promote inclusive education as a human right. That is the Educational Value output: inclusivity.

Turning our attention to the complex web of inputs, the story becomes much messier. In fact, we say that the system is misaligned in Bhutan when it comes to producing inclusivity as an educational value. For example, the curriculum is very fixed and over-subscribed (according to the teachers and students in Bhutan), and this does not allow much room to promote inclusivity when the tenor of the curriculum is one of ‘sink or swim.’ The Bhutanese education system uses a series of examinations at multiple points to pass or fail students, and this competitive and zero-sum educational culture also fails to produce inclusivity as a value when there is a mechanism that is in place to maintain elitism and exclusion.

We talked to many students in Bhutan about their educational experiences and what they hope to gain out of an education. Here’s what one student had to say:

“I guess from my point of view, examination is not like, they’re not checking what we have learned. They’re just checking what we have memorized from the textbook [agreement amongst respondents]. Examinations in Bhutan, like I don’t think it’s helping us to be a better person in the future. They are just checking what we have memorized.” – Student

The teachers we talked to across Bhutan expressed a desire to have happier classrooms, to teach in more student-centered ways, but felt that they couldn’t because of the curriculum, the constant preparation for exams that they did not set themselves, and pressure from school leadership. So while education policy says one thing, the various elements say another. This is how the EVED framework works in identifying the nodes of misalignment.

It is not so simple in terms of reform, however. Remember, the EVED is a repudiation of the input-output model of educational reform. All elements of a complex system need to move together in order for reforms to actually be sustainable. If Bhutanese curriculum were to be altered to be more differentiated, flexible, accommodating, and accessible – all things I would recommend – this cannot be the end of educational reform. By moving curriculum in a certain direction, this also sets in motion changes that need to happen with teachers (who need buy-in, training, support, resources, etc.); school leadership (same as teachers, but maybe even more important in establishing school culture); parents (who need buy-in); all new materials and resources; and on and on through every element. This is exactly why educational reforms inevitably fail, because this kind of work is difficult, lengthy, and requires investment.

The million-dollar question when it comes to reform in any social system: is it better to go big and change it all at once (top-down), or go small and chip away at it one element at a time (bottom-up). I am sorry to say that I don’t really have an answer for you as this is something that I am always debating myself. Having developed the EVED framework, I will say that any reform – big or small – needs to understand how it fits within the entirety of a complex system. Any educational ‘specialist’ that claims to have the one thing that will fix the entire system definitely will not fix it, and may even make it worse. (But, hey, that specialist will keep having more and more work! Sorry, that’s a bit cynical.)

This issue of EdPop was a quick overview of the EVED framework and a brief application. It will take much longer to adequately explain the EVED framework, and even longer to explore various educational values in Bhutan and how certain elements contribute towards them. This will eventually become a full-length book, although the publication of such is TBD.

For Next Week…

This edition of EdPop raised the specter of examinations. Standardized testing is a hot topic of conversation in the education world at the moment, as policy-makers and education officials clash with schools, parents, and advocates around whether or not to reinstate examinations just as schools begin to be back to in-person learning (and after a weird and disjointed school year). In the next issue, I will explore the current debate, and also ask the question: Testing, what is it good for?

Interesting read, Matt.

Have you looked at the Finnish educational system for comparison?